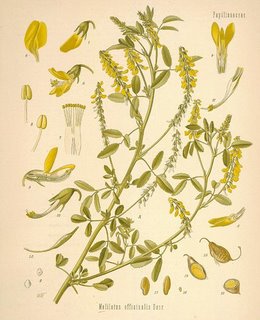

Melilotus officinalis (melilot)

Yellow Melilot. White Melilot. Corn Melilot. King's Clover. Sweet Clover. Plaster Clover. Sweet Lucerne. Wild Laburnum. Hart's Tree.

Part Used

Herb.

The Melilots or Sweet Clovers - formerly known as Melilot Trefoils and assigned, with the common clovers, to the large genus Trifolium, but now grouped in the genus Melilotus - are not very common in Britain, being not truly native, though they have become naturalized, having been extensively cultivated for fodder formerly, especially the common yellow species, Melilotus officinalis (Linn.).

- Although now seldom seen as a crop, having, like the Medick, given place to the Clovers, Sainfoin and Lucerne, Melilot seems, however, to have been a very common crop in the sixteenth century, seeding freely, spreading in a wild condition wherever grown, since Gerard tells us,

- 'for certainty no part of the world doth enjoy so great plenty thereof as England and especially Essex, for I have seen between Sudbury in Suffolke and Clare in Essex and from Clare to Hessingham very many acres of earable pasture overgrowne with the same; in so much that it doth not only spoil their land, but the corn also, as Cockle or Darnel and is a weed that generally spreadeth over that corner of the shire.

The Meliots are perennial herbs, 2 to 4 feet high, found in dry fields and along roadsides, in waste places and chalky banks, especially along railway banks and near lime kilns. The smooth, erect stems are much branched, the leaves placed on alternate sides of the stems are smooth and trifoliate, the leaflets oval. The plants bear long racemes of small, sweet-scented, yellow or white, papilionaceous flowers in the yellow species, the keel of the flower much shorter than the other parts and containing much honey. They are succeeded by broad, black, one-seeded pods, transversely wrinkled.

All species of Melilot, when in flower, have a peculiar sweet odour, which by drying be comes stronger and more agreeable, somewhat like that of the Tonka bean, this similarity being accounted for by the fact that they both contain the same chemical principle, Coumarin, which is also present in new-mown hay and woodruff, which have the identical fragrance.

The name of this genus comes from the words Mel (honey) and lotus (meaning honeylotus), the plants being great favourites of the bees. Popular and local English names are Sweet Clover, King's Clover, Hart's Tree or Plaster Clover, Sweet Lucerne and Wild Laburnum.

The tender foliage makes the plant acceptable to horses and other animals, and it is said that deer browse on it, hence its name 'Hart's Clover. ' Galen used to prescribe Melilot plaster to his Imperial and aristocratic patients when they suffered from inflammatory tumours or swelled joints, and the plant is so used even in the present day in some parts of the Continent.

In one Continental Pharmacopoeia of recent date an emollient application is directed to be made of Melilot, resin, wax, and olive oil.

- Gerard says that:

- 'Melilote boiled in sweet wine untile it be soft, if you adde thereto the yolke of a rosted egge, the meale of Linseed, the roots of Marsh Mallowes and hogs greeace stamped together, and used as a pultis or cataplasma, plaisterwise, doth asswge and soften all manner of swellings.'

Water distilled from the flowers was said to improve the flavour of other ingredients.

There are three varieties of Melilot found in England, the commonest being Melilotus officinalis (Linn.), the Yellow Melilot; M. alba (Desv.), the White Melilot, and M. arvensis (Lamk.), the Corn Melilot, which is found occasionally in waste places in the eastern counties, but is not considered indigenous.

The dried leaves and flowering tops of all three species form the drug used in herbal medicine, though the drug of the German Pharmacopceia is M. officinalis. Two yellowflowered species are, however, often sold under this name, the common M. officinalis, which has hairy pods, and M. arvensis, which has small, smooth pods.

The White Melilot found in waste places in England, particularly on railway banks, is not uncommon, but apparently not permanently established in any of its localities. It differs from M. officinalis by its more slender root and stems, which, however, attain as great a height, by its more slender and lax racemes and smaller flowers, which are about 1/5 inch long and white. The standard is larger than the keel and wings, which alone would distinguish it from M. officinalis. The pods are smaller and free from the hairs clothing those of M. officinalis.

A new kind of Sweet Clover, an annual variety of M. alba, has been discovered in the United States. To distinguish it from the other Sweet Clovers, it is called Hubam, after Professor Hughes, its discoverer, and Alabama, its native state. Some five or six years ago, small samples were distributed by Professor Hughes among various experimental stations, with the result that the superiority of the plant has been generally recognized and its spread has been rapid, over 5,000 acres now being cultivated. The plant has specially valuable characteristics - great resistance to drought, adaptability to a wide variety of soils and climates, abundant seed production, richness in nectar and great fertilizing value to the soil, and has been grown successfully in the United States, Canada, Australia, Italy, and many other countries. The quantity of forage produced from a given acre is second to no other forage plant, and the quality, if properly handled, is excellent. It is of very quick growth and blooms in three to four months after sowing, producing an unusual wealth of honey-making blooms. The flowers remain in bloom for a longer period than almost any other honey-bearing plant, and in the matter of nectar production the quantity is surprising, equal to that of any other honey produced in the United States, and the quality compares favourably with the best honey produced either there or in Great Britain. It is considered that this annual Sweet Clover will one day stand at the head of the list of honey plants of the world, if the present rate of spreading continues.

Parts Used Medicinally

The whole herb is used, dried, for medicinal purposes, the flowering shoots, gathered in May, separated from the main stem and dried in the same manner as Broom tops.

The dried herb has an intensely fragrant odour, but a somewhat pungent and bitterish taste.

Constituents

Coumarin, the crystalline substance developed under the drying process, is the only important constituent, together with its related compounds, hydrocoumaric (melilotic) acid, orthocoumaric acid and melilotic anhydride, or lactone, a fragrant oil.

Medicinal Action and Uses

The herb has aromatic, emollient and carminative properties. It was formerly much esteemed inmedicine as an emollient and digestive and is recommended by Gerard for many complaints, the juice for clearing the eyesight, and, boiled with lard and other ingredients, as an application to wens and ulcers, and mixed with wine, 'it mitigateth the paine of the eares and taketh away the paine of the head.'

Culpepper tells us that the head is to be washed with the distilled herb for loss of senses and apoplexy, and that boiled in wine, it is good for inflammation of the eye or other parts of the body.

- The following recipe is from the Fairfax Still-room book (published 1651):

- 'To make a bath for Melancholy. Take Mallowes, pellitory of the wall, of each three handfulls; Camomell Flowers, Mellilot flowers, of each one handfull, senerick seed one ounce, and boil them in nine gallons of Water untill they come to three, then put in a quart of new milke and go into it bloud warme or something warmer.'

It relieves flatulence and in modern herbal practice is taken internally for this purpose.

The flowers, besides being very useful and attractive to bees, have supplied a perfume, and a water distilled from them has been used for flavouring.

The dried plant has been employed to scent snuff and smoking tobacco and may be laid among linen for the same purpose as lavender. When packed with furs, Melilot is said to act like camphor and preserve them from moths, besides imparting a pleasant fragrance.

'In Switzerland, Melilot abounds in the pastures and is an ingredient in the green Swiss cheese called Schabzieger. The Schabzieger cheese is made by the curd being pressed in boxes with holes to let the whey run out; and when a considerable quantity has been collected and putrefaction begins, it is worked into a paste with a large proportion of the dried herb Melilotus, reduced to a powder. The herb is called in the country dialect "Zieger kraut," curd herb. The paste thus produced is pressed into moulds of the shape of a common flowerpot and the putrefaction being stopped by the aromatic herb, it dries into a solid mass and keeps unchanged for any length of time. When used, it is rasped or grated and the powder mixed with fresh butter is spread upon bread. ' (Syme and Sowerby, English Botany.)