Synonyms

Priest's Crown. Swine's Snout.

Parts Used

Root, leaves.

The Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale, Weber, T. Densleonis, Desf; Leontodon taraxacum, Linn.), though not occurring in the Southern Hemisphere, is at home in all parts of the north temperate zone, in pastures, meadows and on waste ground, and is so plentiful that farmers everywhere find it a troublesome weed, for though its flowers are more conspicuous in the earlier months of the summer, it may be found in bloom, and consequently also prolifically dispersing its seeds, almost throughout the year.

Description

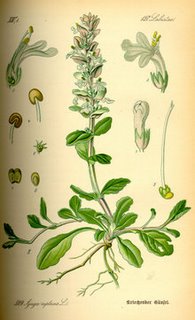

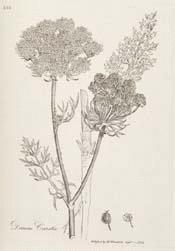

From its thick tap root, dark brown, almost black on the outside though white and milky within, the long jagged leaves rise directly, radiating from it to form a rosette Iying close upon the ground, each leaf being grooved and constructed so that all the rain falling on it is conducted straight to the centre of the rosette and thus to the root which is, therefore, always kept well watered. The maximum amount of water is in this manner directed towards the proper region for utilization by the root, which but for this arrangement would not obtain sufficient moisture, the leaves being spread too close to the ground for the water to penetrate.

The leaves are shiny and without hairs, the margin of each leaf cut into great jagged teeth, either upright or pointing somewhat backwards, and these teeth are themselves cut here and there into lesser teeth. It is this somewhat fanciful resemblance to the canine teeth of a lion that (it is generally assumed) gives the plant its most familiar name of Dandelion, which is a corruption of the French Dent de Lion, an equivalent of this name being found not only in its former specific Latin name Dens leonis and in the Greek name for the genus to which Linnaeus assigned it, Leontodon, but also in nearly all the languages of Europe.

- There is some doubt, however, as to whether it was really the shape of the leaves that provided the original notion, as there is really no similarity between them, but the leaves may perhaps be said to resemble the angular jaw of a lion fully supplied with teeth. Some authorities have suggested that the yellow flowers might be compared to the golden teeth of the heraldic lion, while others say that the whiteness of the root is the feature which provides the resemblance. Flückiger and Hanbury in Pharmacographia, say that the name was conferred by Wilhelm, a surgeon, who was so much impressed by the virtues of the plant that he likened it to Dens leonis. In the Ortus Sanitatis, 1485, under 'Dens Leonis,' there is a monograph of half a page (unaccompanied by any illustration) which concludes:

- 'The Herb was much employed by Master Wilhelmus, a surgeon, who on account of its virtues, likened it to "eynem lewen zan, genannt zu latin Dens leonis" (a lion's tooth, called in Latin Dens leonis).'

In the pictures of the old herbals, for instance, the one in Brunfels' Contrafayt Kreuterbuch, 1532, the leaves very much resemble a lion's tooth. The root is not illustrated at all in the old herbals, as only the herb was used at that time.

- The name of the genus, Taraxacum, is derived from the Greek taraxos (disorder), and akos (remedy), on account of the curative action of the plant. A possible alternative derivation of Taraxacum is suggested in The Treasury of Botany:

- 'The generic name is possibly derived from the Greek taraxo ("I have excited" or "caused") and achos (pain), in allusion to the medicinal effects of the plant.'

There are many varieties of Dandelion leaves; some are deeply cut into segments, in others the segments or lobes form a much less conspicuous feature, and are sometimes almost entire.

The shining, purplish flower-stalks rise straight from the root, are leafless, smooth and hollow and bear single heads of flowers. On picking the flowers, a bitter, milky juice exudes from the broken edges of the stem, which is present throughout the plant, and which when it comes into contact with the hand, turns to a brown stain that is rather difficult to remove.

Each bloom is made up of numerous strapshaped florets of a bright golden yellow. This strap-shaped corolla is notched at the edge into five teeth, each tooth representing a petal, and lower down is narrowed into a claw-like tube, which rests on the singlechambered ovary containing a single ovule. In this tiny tube is a copious supply of nectar, which more than half fills it, and the presence of which provides the incentive for the visits of many insects, among whom the bee takes first rank. The Dandelion takes an important place among honey-producing plants, as it furnishes considerable quantities of both pollen and nectar in the early spring, when the bees' harvest from fruit trees is nearly over. It is also important from the beekeeper's point of view, because not only does it flower most in spring, no matter how cool the weather may be, but a small succession of bloom is also kept up until late autumn, so that it is a source of honey after the main flowers have ceased to bloom, thus delaying the need for feeding the colonies of bees with artificial food.

Many little flies also are to be found visiting the Dandelion to drink the lavishly-supplied nectar. By carefully watching, it has been ascertained that no less than ninety-three different kinds of insects are in the habit of frequenting it. The stigma grows up through the tube formed by the anthers, pushing the pollen before it, and insects smearing themselves with this pollen carry it to the stigmas of other flowers already expanded, thus insuring cross-fertilization. At the base of each flower-head is a ring of narrow, green bracts the involucre. Some of these stand up to support the florets, others hang down to form a barricade against such small insects as might crawl up the stem and injure the bloom without taking a share in its fertilization, as the winged insects do.

The blooms are very sensitive to weather conditions: in fine weather, all the parts are outstretched, but directly rain threatens the whole head closes up at once. It closes against the dews of night, by five o'clock in the evening, being prepared for its night's sleep, opening again at seven in the morning though as this opening and closing is largely dependent upon the intensity of the light, the time differs somewhat in different latitudes and at different seasons.

When the whole head has matured, all the florets close up again within the green sheathing bracts that lie beneath, and the bloom returns very much to the appearance it had in the bud. Its shape being then somewhat reminiscent of the snout of a pig, it is termed in some districts 'Swine's Snout.' The withered, yellow petals are, however soon pushed off in a bunch, as the seeds, crowned with their tufts of hair, mature, and one day, under the influence of sun and wind the 'Swine's Snout' becomes a large gossamer ball, from its silky whiteness a very noticeable feature. It is made up of myriads of plumed seeds or pappus, ready to be blown off when quite ripe by the slightest breeze, and forms the 'clock' of the children, who by blowing at it till all the seeds are released, love to tell themselves the time of day by the number of puffs necessary to disperse every seed. When all the seeds have flown, the receptacle or disc on which they were placed remains bare, white, speckled and surrounded by merely the drooping remnants of the sheathing bracts, and we can see why the plant received another of its popular names, 'Priest's Crown,' common in the Middle Ages, when a priest's shorn head was a familiar object.

Small birds are very fond of the seeds of the Dandelion and pigs devour the whole plant greedily. Goats will eat it, but sheep and cattle do not care for it, though it is said to increase the milk of cows when eaten by them. Horses refuse to touch this plant, not appreciating its bitter juice. It is valuable food for rabbits and may be given them from April to September forming excellent food in spring and at breeding seasons in particular.

The young leaves of the Dandelion make an agreeable and wholesome addition to spring salads and are often eaten on the Continent, especially in France. The full-grown leaves should not be taken, being too bitter, but the young leaves, especially if blanched, make an excellent salad, either alone or in combination with other plants, lettuce, shallot tops or chives.

Young Dandelion leaves make delicious sandwiches, the tender leaves being laid between slices of bread and butter and sprinkled with salt. The addition of a little lemon-juice and pepper varies the flavour. The leaves should always be torn to pieces, rather than cut, in order to keep the flavour.

John Evelyn, in his Acetana, says: 'With thie homely salley, Hecate entertained Theseus.' In Wales, they grate or chop up Dandelion roots, two years old, and mix them with the leaves in salad. The seed of a special broad-leaved variety of Dandelion is sold by seedsmen for cultivation for salad purposes. Dandelion can be blanched in the same way as endive, and is then very delicate in flavour. If covered with an ordinary flower-pot during the winter, the pot being further buried under some rough stable litter, the young leaves sprout when there is a dearth of saladings and prove a welcome change in early spring. Cultivated thus, Dandelion is only pleasantly bitter, and if eaten while the leaves are quite young, the centre rib of the leaf is not at all unpleasant to the taste. When older the rib is tough and not nice to eat. If the flower-buds of plants reserved in a corner of the garden for salad purposes are removed at once and the leaves carefully cut, the plants will last through the whole winter.

The young leaves may also be boiled as a vegetable, spinach fashion, thoroughly drained, sprinkled with pepper and salt, moistened with soup or butter and served very hot. If considered a little too bitter, use half spinach, but the Dandelion must be partly cooked first in this case, as it takes longer than spinach. As a variation, some grated nutmeg or garlic, a teaspoonful of chopped onion or grated lemon peel can be added to the greens when they are cooked. A simple vegetable soup may also be made with Dandelions.

The dried Dandelion leaves are also employed as an ingredient in many digestive or diet drinks and herb beers. Dandelion Beer is a rustic fermented drink common in many parts of the country and made also in Canada. Workmen in the furnaces and potteries of the industrial towns of the Midlands have frequent resource to many of the tonic Herb Beers, finding them cheaper and less intoxicating than ordinary beer, and Dandelion stout ranks as a favourite. An agreeable and wholesome fermented drink is made from Dandelions, Nettles and Yellow Dock.

In Berkshire and Worcestershire, the flowers are used in the preparation of a beverage known as Dandelion Wine. This is made by pouring a gallon of boiling water over a gallon of the flowers. After being well stirred, it is covered with a blanket and allowed to stand for three days, being stirred again at intervals, after which it is strained and the liquor boiled for 30 minutes, with the addition of 3 1/2 lb. of loaf sugar, a little ginger sliced, the rind of 1 orange and 1 lemon sliced. When cold, a little yeast is placed in it on a piece of toast, producing fermentation. It is then covered over and allowed to stand two days until it has ceased 'working,' when it is placed in a cask, well bunged down for two months before bottling. This wine is suggestive of sherry slightly flat, and has the deserved reputation of being an excellent tonic, extremely good for the blood.

The roasted roots are largely used to form Dandelion Coffee, being first thoroughly cleaned, then dried by artificial heat, and slightly roasted till they are the tint of coffee, when they are ground ready for use. The roots are taken up in the autumn, being then most fitted for this purpose. The prepared powder is said to be almost indistinguishable from real coffee, and is claimed to be an improvement to inferior coffee, which is often an adulterated product. Of late years, Dandelion Coffee has come more into use in this country, being obtainable at most vegetarian restaurants and stores. Formerly it used occasionally to be given for medicinal purposes, generally mixed with true coffee to give it a better flavour. The ground root was sometimes mixed with chocolate for a similar purpose. Dandelion Coffee is a natural beverage without any of the injurious effects that ordinary tea and coffee have on the nerves and digestive organs. It exercises a stimulating influence over the whole system, helping the liver and kidneys to do their work and keeping the bowels in a healthy condition, so that it offers great advantages to dyspeptics and does not cause wakefulness.

Parts Used Medicinally

The root, fresh and dried, the young tops. All parts of the plant contain a somewhat bitter, milky juice (latex), but the juice of the root being still more powerful is the part of the plant most used for medicinal purposes.

History

The first mention of the Dandelion as a medicine is in the works of the Arabian physicians of the tenth and eleventh centuries, who speak of it as a sort of wild Endive, under the name of Taraxcacon. In this country, we find allusion to it in the Welsh medicines of the thirteenth century. Dandelion was much valued as a medicine in the times of Gerard and Parkinson, and is still extensively employed.

Dandelion roots have long been largely used on the Continent, and the plant is cultivated largely in India as a remedy for liver complaints.

The root is perennial and tapering, simple or more or less branched, attaining in a good soil a length of a foot or more and 1/2 inch to an inch in diameter. Old roots divide at the crown into several heads. The root is fleshy and brittle, externally of a dark brown, internally white and abounding in an inodorous milky juice of bitter, but not disagreeable taste.

Only large, fleshy and well-formed roots should be collected, from plants two years old, not slender, forked ones. Roots produced in good soil are easier to dig up without breaking, and are thicker and less forked than those growing on waste places and by the roadside. Collectors should, therefore only dig in good, free soil, in moisture and shade, from meadow-land. Dig up in wet weather, but not during frost, which materially lessens the activity of the roots. Avoid breaking the roots, using a long trowel or a fork, lifting steadily and carefully. Shake off as much of the earth as possible and then cleanse the roots, the easiest way being to leave them in a basket in a running stream so that the water covers them, for about an hour, or shake them, bunched, in a tank of clean water. Cut off the crowns of leaves, but be careful in so doing not to leave any scales on the top. Do not cut or slice the roots or the valuable milky juice on which their medicinal value depends will be wasted by bleeding.

Cultivation

As only large, well-formed roots are worth collecting, some people prefer to grow Dandelions as a crop, as by this means large roots are insured and they are more easily dug, generally being ploughed up. About 4 lb. of seed to the acre should be allowed, sown in drills, 1 foot apart. The crops should be kept clean by hoeing, and all flower-heads should be picked off as soon as they appear, as otherwise the grower's own land and that of his neighbours will be smothered with the weed when the seeds ripen. The yield should be 4 or 5 tons of fresh roots to the acre in the second year. Dandelion roots shrink very much in drying, losing about 76 per cent of their weight, so that 100 parts of fresh roots yield only about 22 parts of dry material. Under favourable conditions, yields at the rate of 1,000 to 1,500 lb. of dry roots per acre have been obtained from second-year plants cultivated.

Dandelion root can only be economically collected when a meadow in which it is abundant is ploughed up. Under such circumstances the roots are necessarily of different ages and sizes, the seeds sowing themselves in successive years. The roots then collected after washing and drying, have to be sorted into different grades. The largest, from the size of a lead pencil upwards, are cut into straight pieces 2 to 3 inches long, the smaller side roots being removed, these are sold at a higher price as the finest roots. The smaller roots fetch a less price, and the trimmings are generally cut small, sold at a lower price and used for making Dandelion Coffee. Every part of the root is thus used. The root before being dried should have every trace of the leaf-bases removed as their presence lessens the value of the root.

In collecting cultivated Dandelion advantage is obtained if the seeds are all sown at one time, as greater uniformity in the size of the root is obtainable, and in deep soil free from stones, the seedlings will produce elongated, straight roots with few branches, especially if allowed to be somewhat crowded on the same principles that coppice trees produce straight trunks. Time is also saved in digging up the roots which can thus be sold at prices competing with those obtained as the result of cheaper labour on the Continent. The edges of fields when room is allowed for the plough-horses to turn, could easily be utilized if the soil is good and free from stones for both Dandelion and Burdock, as the roots are usually much branched in stony ground, and the roots are not generally collected until October when the harvest is over. The roots gathered in this month have stored up their food reserve of Inulin, and when dried present a firm appearance, whilst if collected in spring, when the food reserve in the root is used up for the leaves and flowers, the dried root then presents a shrivelled and porous appearance which renders it unsaleable. The medicinal properties of the root are, therefore, necessarily greater in proportion in the spring. Inulin being soluble in hot water, the solid extract if made by boiling the root, often contains a large quantity of it, which is deposited in the extract as it cools.

The roots are generally dried whole, but the largest ones may sometimes be cut transversely into pieces 3 to 6 inches long. Collected wild roots are, however, seldom large enough to necessitate cutting. Drying will probably take about a fortnight. When finished, the roots should be hard and brittle enough to snap, and the inside of the roots white, not grey

The roots should be kept in a dry place after drying, to avoid mould, preferably in tins to prevent the attacks of moths and beetles. Dried Dandelion is exceedingly liable to the attacks of maggots and should not be kept beyond one season.

Dried Dandelion root is 1/2 inch or less in thickness, dark brown, shrivelled, with wrinkles running lengthwise, often in a spiral direction; when quite dry, it breaks easily with a short, corky fracture, showing a very thick, white bark, surrounding a wooden column. The latter is yellowish, very porous, without pith or rays. A rather broad but indistinct cambium zone separates the wood from the bark, which latter exhibits numerous well-defined, concentric layers, due to the milk vessels. This structure is quite characteristic and serves to distinguish Dandelion roots from other roots like it. There are several flowers easily mistaken for the Dandelion when in blossom, but these have either hairy leaves or branched flower-stems, and the roots differ either in structure or shape.

Dried Dandelion root somewhat resembles Pellitory and Liquorice roots, but Pellitory differs in having oil glands and also a large radiate wood, and Liquorice has also a large radiate wood and a sweet taste.

The root of Hawkbit (Leontodon hispidus) is sometimes substituted for Dandelion root. It is a plant with hairy, not smooth leaves, and the fresh root is tough, breaking with difficulty and rarely exuding much milky juice. Some kinds of Dock have also been substituted, and also Chicory root. The latter is of a paler colour, more bitter and has the laticiferous vessels in radiating lines. In the United States it is often substituted for Dandelion. Dock roots have a prevailing yellowish colour and an astringent taste.

During recent years, a small form of a Dandelion root has been offered by Russian firms, who state that it is sold and used as Dandelion in that country. This root is always smaller than the root of T. officinale, has smaller flowers, and the crown of the root has often a tuft of brown woolly hairs between the leaf bases at the crown of the root, which are never seen in the Dandelion plant in this country, and form a characteristic distinction, for the root shows similar concentric, horny rings in the thick white bark as well as a yellow porous woody centre. These woolly hairs are mentioned in Greenish's Materia Medica, and also in the British Pharmaceutical Codex, as a feature of Dandelion root, but no mention is made of them in the Pharmacographia, nor in the British Pharmacopceia or United States Pharmacopceia, and it is probable, therefore, that Russian specimens have been used for describing the root, and that the root with brown woolly hairs belongs to some other species of Taraxacum.

Chemical Constituents

The chief constituents of Dandelion root are Taraxacin, acrystalline, bitter substance, of which the yield varies in roots collected at different seasons, and Taraxacerin, an acrid resin, with Inulin (a sort of sugar which replaces starch in many of the Dandelion family, Compositae), gluten, gum and potash. The root contains no starch, but early in the year contains much uncrystallizable sugar and laevulin, which differs from Inulin in being soluble in cold water. This diminishes in quantity during the summer and becomes Inulin in the autumn. The root may contain as much as 24 per cent. In the fresh root, the Inulin is present in the cell-sap, but in the dry root it occurs as an amorphodus, transparent solid, which is only slightly soluble in cold water, but soluble in hot water.

There is a difference of opinion as to the best time for collecting the roots. The British Pharmacopceia considers the autumn dug root more bitter than the spring root, and that as it contains about 25 per cent insoluble Inulin, it is to be preferred on this account to the spring root, and it is, therefore, directed that in England the root should be collected between September and February, it being considered to be in perfection for Extract making in the month of November.

Bentley, on the other hand, contended that it is more bitter in March and most of all in July, but that as in the latter month it would generally be inconvenient for digging it, it should be dug in the spring, when the yield of Taraxacin, the bitter soluble principle, is greatest.

On account of the variability of the constituents of the plant according to the time of year when gathered, the yield and composition of the extract are very variable. If gathered from roots collected in autumn, the resulting product yields a turbid solution with water; if from spring-collected roots, the aqueous solution will be clear and yield but very little sediment on standing, because of the conversion of the Inulin into Laevulose and sugar at this active period of the plant's life.

In former days, Dandelion Juice was the favourite preparation both in official and domestic medicine. Provincial druggists sent their collectors for the roots and expressed the juice while these were quite fresh. Many country druggists prided themselves on their Dandelion Juice. The most active preparations of Dandelion, the Juice (Succus Taraxaci) and the Extract (Extractum Taraxaci), are made from the bruised fresh root. The Extract prepared from the fresh root is sometimes almost devoid of bitterness. The dried root alone was official in the United States Pharmacopoeia.

The leaves are not often used, except for making Herb-Beer, but a medicinal tincture is sometimes made from the entire plant gathered in the early summer. It is made with proof spirit.

When collecting the seeds care should be taken when drying them in the sun, to cover them with coarse muslin, as otherwise the down will carry them away. They are best collected in the evening, towards sunset, or when the damp air has caused the heads to close up.

The tops should be cut on a dry day, when quite free of rain or dew, and all insect-eaten or stained leaves rejected.

Medicinal Action and Uses

Diuretic, tonic and slightly aperient. It is a general stimulant to the system, but especially to the urinary organs, and is chiefly used in kidney and liver disorders.

Dandelion is not only official but is used in many patent medicines. Not being poisonous, quite big doses of its preparations may be taken. Its beneficial action is best obtained when combined with other agents.

The tincture made from the tops may be taken in doses of 10 to 15 drops in a spoonful of water, three times daily.

It is said that its use for liver complaints was assigned to the plant largely on the doctrine of signatures, because of its bright yellow flowers of a bilious hue.

In the hepatic complaints of persons long resident in warm climates, Dandelion is said to afford very marked relief. A broth of Dandelion roots, sliced and stewed in boiling water with some leaves of Sorrel and the yolk of an egg, taken daily for some months, has been known to cure seemingly intractable cases of chronic liver congestion.

A strong decoction is found serviceable in stone and gravel: the decoction may be made by boiling 1 pint of the sliced root in 20 parts of water for 15 minutes, straining this when cold and sweetening with brown sugar or honey. A small teacupful may be taken once or twice a day.

Dandelion is used as a bitter tonic in atonic dyspepsia, and as a mild laxative in habitual constipation. When the stomach is irritated and where active treatment would be injurious, the decoction or extract of Dandelion administered three or four times a day, will often prove a valuable remedy. It has a good effect in increasing the appetite and promoting digestion.

Dandelion combined with other active remedies has been used in cases of dropsy and for induration of the liver, and also on the Continent for phthisis and some cutaneous diseases. A decoction of 2 OZ. of the herb or root in 1 quart of water, boiled down to a pint, is taken in doses of one wineglassful every three hours for scurvy, scrofula, eczema and all eruptions on the surface of the body.

Preparations and Dosages

Fluid extract, B.P., 1/2 to 2 drachms. Solid extract, B.P. 5 to 15 grains. Juice, B.P., 1 to 2 drachms. Leontodin, 2 to 4 grains.

Dandelion Tea

Infuse 1 OZ. of Dandelion in a pint of boiling water for 10 minutes; decant, sweeten with honey, and drink several glasses in the course of the day. The use of this tea is efficacious in bilious affections, and is also much approved of in the treatment of dropsy.

Or take 2 OZ. of freshly-sliced Dandelion root, and boil in 2 pints of water until it comes to 1 pint; then add 1 OZ. of compound tincture of Horseradish. Dose, from 2 to 4 OZ. Use in a sluggish state of the liver.

Or 1 OZ. Dandelion root, 1 OZ. Black Horehound herb, 1/2 OZ. Sweet Flag root, 1/4 OZ. Mountain Flax. Simmer the whole in 3 pints of water down to 1 1/2 pint, strain and take a wineglassful after meals for biliousness and dizziness.

For Gall Stones

1 OZ. Dandelion root, 1 OZ. Parsley root, 1 OZ. Balm herb, 1/2 OZ. Ginger root, 1/2 OZ. Liquorice root. Place in 2 quarts of water and gently simmer down to 1 quart, strain and take a wineglassful every two hours.

For a young child suffering from jaundice: 1 OZ. Dandelion root, 1/2 oz. Ginger root, 1/2 oz. Caraway seed, 1/2 oz. Cinnamon bark, 1/4 oz. Senna leaves. Gently boil in 3 pints of water down to 1 1/2 pint, strain, dissolve 1/2 lb. sugar in hot liquid, bring to a boil again, skim all impurities that come to the surface when clear, put on one side to cool, and give frequently in teaspoonful doses.

A Liver and Kidney Mixture

1 OZ. Broom tops, 1/2 oz. Juniper berries, 1/2 oz. Dandelion root, 1 1/2 pint water. Boil in gredients for 10 minutes, then strain and adda small quantity of cayenne. Dose, 1 tablespoonful, three times a day.

A Medicine for Piles

1 OZ. Long-leaved Plantain, 1 OZ. Dandelion root, 1/2 oz. Polypody root, 1 OZ. Shepherd's Purse. Add 3 pints of water, boil down to half the quantity, strain, and add 1 OZ. of tincture of Rhubarb. Dose, a wineglassful three times a day. Celandine ointment to be applied at same time.

In Derbyshire, the juice of the stalk is applied to remove warts.